Let’s talk about age-based learning. It’s how we structure our schools and for the most part, our teaching. But with all the knowledge, data and strategies we have in education today is it really the best way forward for our students? Should we determine what a student is learning based on their age, or their ability instead?

Sink or swim

Think back to swimming lessons in primary school. You didn’t move from one level to another until you had demonstrated mastery. For some that meant moving from Level 1 to Junior Squad in a matter of months. For others, it meant floating in Level 2 for the duration of primary years.

The level you were in was purely based on your skill. The teacher would not rip off your floaties and push you onto a diving board just because you’re a year older — that’s just dangerous. And they’re not going to keep running a student through laps on a kickboard when they can swim 50 metres backstroke, just because they haven’t had their birthday yet.

But this sink or swim approach is exactly the one we use in our classrooms. We push students who haven’t mastered a concept up to the next level and we keep others swimming circles around content they are beyond.

That doesn’t mean we should throw the curriculum out the door. It means we should look at the reasons why age-based learning doesn’t work so we can change our approach and support our students to grow.

Ignoring the spread of ability

The age-based approach was introduced in the 1800s, when we didn’t know much about learning, human development or the brain. We’ve come a long way since then.

Today, we know that students learn maths on a continuum. They must understand one concept before they can move on to the next. Because if they don’t master the foundations, learning new concepts further along can be very difficult or even impossible.

The age-based model doesn’t consider this. It places a Year 7 teacher in front of their Year 7 class to deliver a full year of Year 7 curriculum. And every student is expected to learn all of that curriculum in one school year. Because when they head into Year 8, they repeat the process.

There are many problems with this. Firstly, it assumes that every student in the Year 7 classroom has mastered all of the curriculum they’ve been exposed to up to the Year 7 level. In reality, every student will walk into the first day of class with completely different abilities in maths.

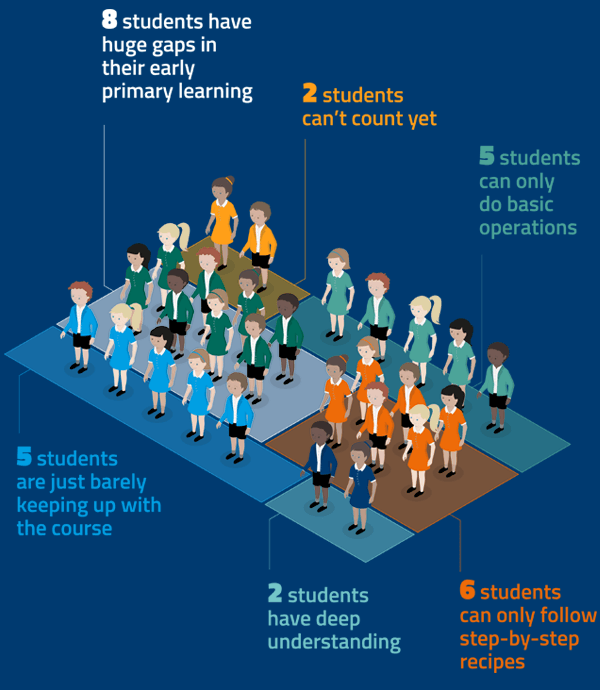

In fact, in a typical Year 7 classroom there is an eight-year spread of ability ranging from students who struggle to count, to students who have a deep mathematical understanding and lack challenge from aged-based content.

Moving students before they’re ready

So we’re faced with a class of students, each with different gaps and competencies, yet we teach them the same content. That might be okay, if the age-based approach didn’t have a second flaw.

Using the approach, Terms are structured so that we set timeframes for learning specific content and students are expected to meet these ‘deadlines’ for learning. In other words, every student must master long division in two weeks because that’s the amount of time we’ve allowed to do it. But for a lot of students, the allocated time isn’t enough.

Teachers are expected to cover a lot of curriculum over the course of a year. So as the weeks pass us by we have to move students along, regardless of whether they’re ready or not.

It’s not because we want to, of course. It’s because that’s the way it works. And it happens term after term, year after year.

In fact, this is probably what causes the spread of ability in the first place. It’s just compounded over time. So students who are behind fall even further, without much opportunity to catch up.

The path to disengagement

When you consider the wide spread of ability in the classroom, there are a number of students who will be learning content that they’re not ready to learn. There will also be students who will be more advanced than their peers and won’t be challenged enough by the content they’re learning.

This is a recipe for disengagement. It can lead to behavioural problems and a strong dislike for maths. After all, students don’t start school disliking maths. But many of them leave school feeling that way.

Some students, however, might not completely disengage, but they do lack interest or perceive maths as difficult. So instead of actively engaging in maths class they turn to memorising formulas.

We know rote learning is not good for students. Instead they should be thinking critically and creatively. But when students are disengaged with maths — when they don’t like it or don’t ‘get it’ — it can be easier to get through by learning a formula and trying to apply it, rather than actually understanding the concept.

A growing problem

When it comes down to it, the challenges that age-based learning present become a cycle that ultimately prevents students from growing in maths. They start the year learning content they’re not ready for, they get moved on too quickly and fall behind further, then they disengage from maths.

This obviously leads to poorer outcomes for our students, but it also has wider implications.

The number of Australian students choosing to study maths in the senior years of high school and beyond is shrinking. According to projections by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, employment is predicted to increase in professional, scientific and technical services by 12% and in health care by almost 16% over the next five years. Meanwhile, the STEM pipeline of primary and secondary students, graduates and job seekers is declining.

In fact, data from Australia’s 2015 PISA results show that 22% of Australian 15 year-olds fell short of PISA’s minimum proficient standard (Level 2), compared to only 9% of students in the world’s five best performing education systems. The types of opportunities that students will have in the future workforce are directly linked to the competencies they have attained by age 15. Making the lack of mathematically skilled job seekers not at all surprising.

The way forward

If age-based learning is outdated and ineffective, how do we move forward? We can’t rearrange our school system overnight, can we?

While systemic change is going to take time, we can increase the impact of our teaching practices to improve student outcomes with a different approach in our classrooms — personalised learning.

Ask any teacher and they’re likely to tell you that personalised learning can have dramatic results on student progress.

When students experience this type of teaching they often don’t just progress in their learning, they become more engaged. When they’re learning the maths that they’re ready to learn, students can experience success and become more confident in their mathematical abilities, leading to more interest in the subject.

This ‘goldilocks’ content — not too hard, but not too easy — is a vital part of personalised learning. Students should be challenged and engaged by a problem, but they must also have the foundation knowledge to be capable of solving it.

Hitting this point of need can be difficult to do alone. We need data on each student’s gaps and competencies to determine what they’re ready to learn. Plus ongoing assessments that monitor progress and define what students should learn next.

An age-based alternative

This is one of the reasons that schools across Australia are implementing Maths Pathway — to support teachers to target their teaching using a holistic approach. The model leverages technology to deliver diagnostics and ongoing formative assessments. This provides teachers with live, actionable student data that’s easy to access. It also ensures students get the right content, which consists of carefully scaffolded learning activities that work to build students’ understanding, fluency, problem-solving and reasoning skills. Leaving teachers with more time to focus on what matters — teaching their students.

Research shows that personalised learning works and data from Maths Pathway students is consistent with this. Students using the model master twice as much curriculum in one year as they would in a traditional classroom. Better still, this progress is sustained by students too.

Giving students the opportunity to grow

These examples show us that meeting students at their level — rather than at their age — gives them the opportunity to grow in maths. It means they can build on their existing understanding, regardless of where they start from. Giving them the opportunity to truly master concepts and build a solid mathematical understanding.

If you want to learn more about how Maths Pathway is supporting more than 3,700 teachers to deliver personalised learning to 83,000 students complete the form below or read more about our model here.